The Act is a vidoegame about controlling your body language. It's experimental and accessible; short yet satisfying.

While so many other games promote extremes of being completely good or evil, killing everyone and finding everything, it's refreshing to see a game promote moderation. There's no correct dialogue option; you actually have to watch the faces of the NPCs to determine how you should act. Originally, the arcade game had a knob to twist your character from shy to gregarious, but the iOS port uses swipes.

A minute in and you can get a feel for the gameplay. The other amazing thing about this game is that it's all animated, old-school Disney-style. While there are some frustrating parts, overall, I was very impressed with the exploration of this new style of interaction. I'd love to see a body-language slider in an RPG, but given how intensive it is to animate, I might have to settle for tone brackets like (sarcastic) and (imploring).

Friday, July 27, 2012

Thursday, July 26, 2012

Jigsaw Puzzle Design: It's about being able to predict what pieces fit

I recently had the pleasure of putting together a wooden jigsaw puzzle. It was so much more fun than the old cardboard puzzles. I got to thinking about why cardboard puzzles suck and thought I could do a little analysis for you.

|

| Ravensburger puts out like a million of these |

|

| mini Japanese puzzle has even fewer piece types |

This is from your typical cardboard puzzle. There are about six major piece types, and some rarer border and corner pieces. Since all the pieces look the same, you are pretty much stuck to looking at the colors on the pieces for figuring out where they go (oh, and the border-first thing). Having fun with this kind of puzzle relies heavily on having a diverse puzzle-picture, and having access to that picture.

|

| Wentworth puzzle |

These pieces are from a puzzle I picked up in England. Since each piece's shape is very different from the others, it's possible to build this kind of puzzle by looking at the shapes alone. There are edge pieces, but some middle pieces also have straight edges. The pieces are wooden and have a satisfying feeling of fitting, unlike cardboard pieces where the cardboard gives a little even when you're putting together pieces that fit. There are still some conventional shapes, for which you can usually guess which way is up. Little "whimsy pieces" are shaped like things and it's easy to tell which pieces fit around them (for instance, you can see the silhouette of the horse-rider's head in one of the pieces here).

|

| the border is scalloped. This is a corner taken apart. |

This moment of epiphany, when I could see the solution before enacting it, is crucial to a good puzzle game. It's the same feeling I get when I play falling-block games or things like Portal and Catherine. It's what makes puzzles fun for me.

|

| piece orientation is unpredictable. Artifact Jigsaw. |

Another aspect of jigsaw puzzles is that I've liked is that they're easily multiplayer. If someone else sees you working on a jigsaw puzzle, they can instantly tell how far you are and what kind of puzzle it is. Piecing together a puzzle isn't timed, and it's cooperative. You can start without having to wait for it to load and play for as short or as long as you like (if you're willing to re-do your puzzle). I haven't really found a puzzle game that's as good at multiplayer as a good old jigsaw puzzle.

Monday, July 23, 2012

Of tourism and game-playing

"I'm kind of doing a speed run of Journey," my husband, Adam, explained. For each complete run through of the game (up to... four times?), the decoration on your robe gets more elaborate. A speed run seemed like a logical way to enjoy the game a different way and get the cool robe addition. But yet, somehow a speedrun of Journey seems inimical to the game's aesthetics.

In the same way, my speedrun of England and Paris was completely typical of tourism, but I felt sometimes like I was missing the point of enjoying a new place, or any place. There is an urge to see all the vital sights--sights that, once seen, can be checked off a list; their countries stamped in one's passport. I'm very grateful that I had to opportunity to go to England and Paris, and I realize that everyone who writes feels the desire to write about their experiences abroad as if it is something new that no one else noticed. I know that my experiences are common. I submit that the common problems with tourism are also common to playing classic or popular videogames.

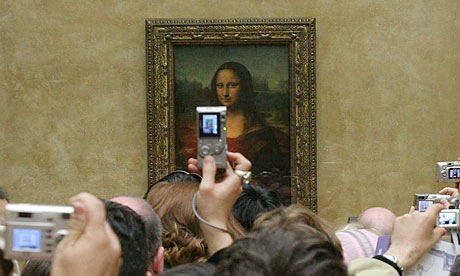

At the Louvre, we must see the Mona Lisa, if only to say we've seen it. Her admirers petition her with cameras, increasing her immortality with each replication. I see other works I recognize; it's like seeing a celebrity, except it frequently looks exactly the same as your mental image does. Sure, the background details come out a bit better, and you can see the frame and the brushstrokes better, but everyone is in the same position. The glass pyramid looks as see-through as ever. Liberty Leading the People still has her breast exposed. And we must take a photo to show that we've been there. Or perhaps all these photos are so we can enjoy the details later, from the comfort of our homes. Taking photos becomes a way to relieve the anxiety that we aren't taking it all in--because maybe the camera is?

And of course, while I'm there at the Louvre, I'm thinking about the sights we'll see in the next few days, because these things must be planned--a simple pain of touring. After my speedrun of the Louvre, I didn't have time to go back and do a hardcore playthrough where I explored every hallway. My time and energy were spent.

Luckily, videogames have their entire world in their files. The anxiety isn't that we won't have the opportunity to see everything, but that we won't have time to beat them. Similarly, while playing one game, it's easy to think anxiously about its completion and what exciting game one will play after that one is done with. The text speed is impossibly slow and your character can't run fast enough. Playing the game becomes a chore.

You're familiar with this feeling. I'm trying to become more aware of it. When I feel like playing a game is a chore, I feel like I should stop playing it. But there's a balance to have here--some chores can be soothing in their repetition (like grinding), and sometimes pushing through a boring part of a game lets one enjoy its especially nice parts (like how even though walking seems impossibly slow in Dear Esther, getting to see the caves is completely worth it for the visual spectacle alone).

Of course, there's a similar problem with tourism. Standing in line for over an hour at Versailles, I felt like tourism was a chore (a chore of the rich and privileged, but a chore nonetheless). But I felt like it was worth it to see the gaudy opulence that spurred a revolution and the stately, over-the-top gardens that went with it. I don't know how to balance being "in the moment" with "planning ahead so you don't get bored/stranded/waste time." But I do know it's a balance I strive for, in tourism, videogame playing, and in the rest of my life. I hope to explore Utah a little more--a place where I have the time and energy to do a "hardcore playthrough."

In the same way, my speedrun of England and Paris was completely typical of tourism, but I felt sometimes like I was missing the point of enjoying a new place, or any place. There is an urge to see all the vital sights--sights that, once seen, can be checked off a list; their countries stamped in one's passport. I'm very grateful that I had to opportunity to go to England and Paris, and I realize that everyone who writes feels the desire to write about their experiences abroad as if it is something new that no one else noticed. I know that my experiences are common. I submit that the common problems with tourism are also common to playing classic or popular videogames.

|

| credit |

And of course, while I'm there at the Louvre, I'm thinking about the sights we'll see in the next few days, because these things must be planned--a simple pain of touring. After my speedrun of the Louvre, I didn't have time to go back and do a hardcore playthrough where I explored every hallway. My time and energy were spent.

Luckily, videogames have their entire world in their files. The anxiety isn't that we won't have the opportunity to see everything, but that we won't have time to beat them. Similarly, while playing one game, it's easy to think anxiously about its completion and what exciting game one will play after that one is done with. The text speed is impossibly slow and your character can't run fast enough. Playing the game becomes a chore.

You're familiar with this feeling. I'm trying to become more aware of it. When I feel like playing a game is a chore, I feel like I should stop playing it. But there's a balance to have here--some chores can be soothing in their repetition (like grinding), and sometimes pushing through a boring part of a game lets one enjoy its especially nice parts (like how even though walking seems impossibly slow in Dear Esther, getting to see the caves is completely worth it for the visual spectacle alone).

Of course, there's a similar problem with tourism. Standing in line for over an hour at Versailles, I felt like tourism was a chore (a chore of the rich and privileged, but a chore nonetheless). But I felt like it was worth it to see the gaudy opulence that spurred a revolution and the stately, over-the-top gardens that went with it. I don't know how to balance being "in the moment" with "planning ahead so you don't get bored/stranded/waste time." But I do know it's a balance I strive for, in tourism, videogame playing, and in the rest of my life. I hope to explore Utah a little more--a place where I have the time and energy to do a "hardcore playthrough."

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)